Susan Hockfield, PhD, the first woman to lead the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), redefined what it means to pioneer change in academia and science.

While her groundbreaking appointment as the first female president in 2004 garnered significant attention, her status as a biologist at the helm of a predominantly engineering-focused institution reshaped MIT’s trajectory.

From championing interdisciplinary collaboration to fostering innovations in clean energy and cancer research, Hockfield's leadership cemented her legacy as a transformative force in science and education.

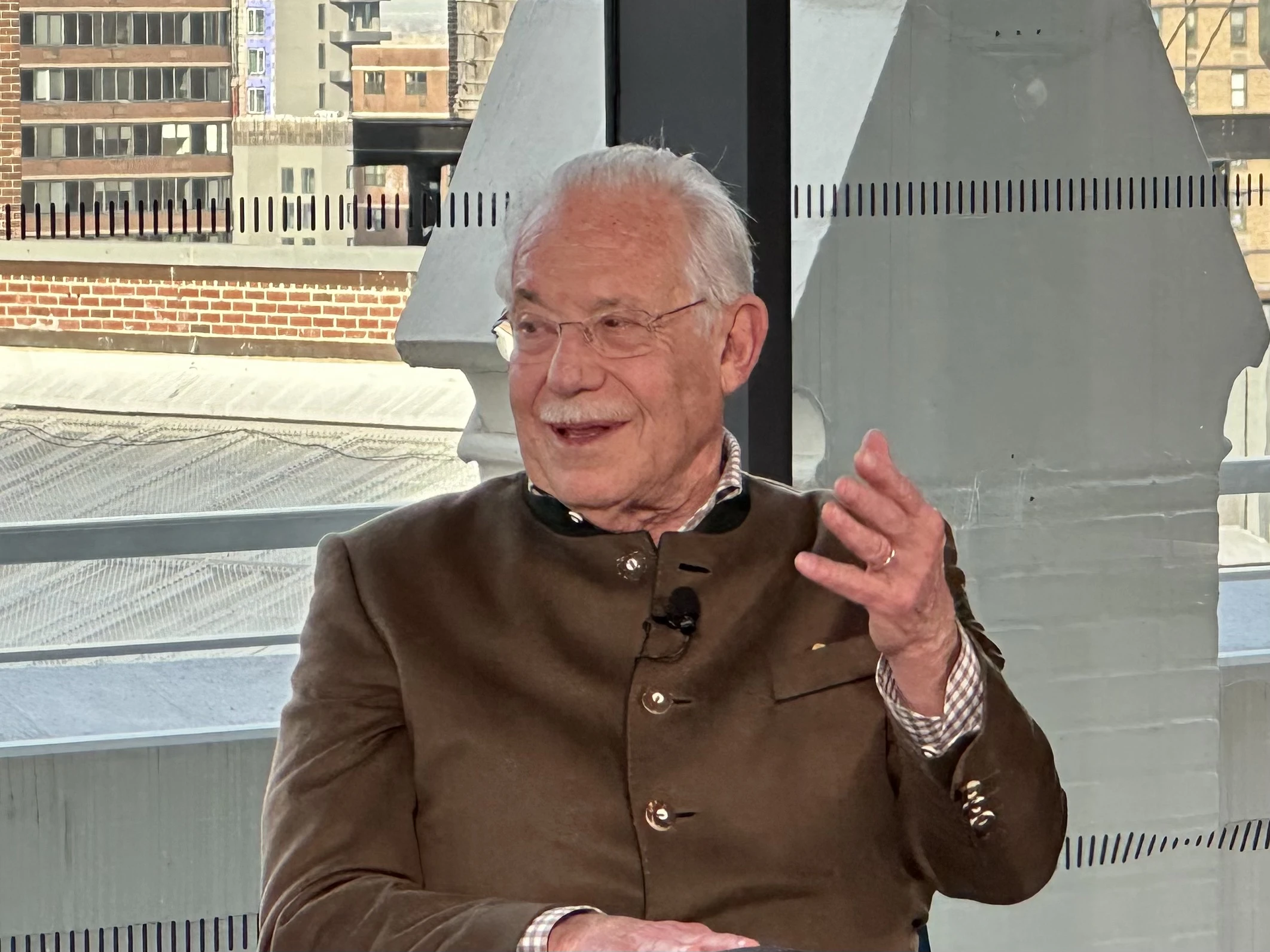

Hockfield spoke at the 2024 BioFuture meeting and recently joined Cure CEO Seema Kumar to discuss women in science, building innovation ecosystems, gene and cellular therapies, and what "cure" means to her. Here are five takeaways from their conversation.

1. Hockfield's career as a biologist raised more eyebrows than being a woman when she became the first female President of MIT in 2004.

"When people reflect on my having been the first woman to serve as President of MIT and the first biologist, the more disruptive of those two qualities was being a biologist," Hockfield noted. "MIT is an engineering institution, and people carry that very proudly. We do have a full range of academic activities, but still, in our hearts, MIT is about engineering."

It made no difference, however. As President, she shaped national policy on energy technology and manufacturing and championed breakthroughs in fields from clean energy to cancer. At MIT, her vision drove several new initiatives, including founding the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and the MIT Energy Initiative. There has also been increased collaboration between biologists and engineers at the university.

2. Female faculty lag in company formation and entrepreneurship.

When Hockfield arrived at MIT, about half of the undergraduates and a third of the faculty were women.

"We've made a huge amount of progress, but we're not where we need to be," she maintained.

MIT biologist Nancy Hopkins, PhD, found that MIT's female investigators had less square footage in their labs and earned less compensation than men — something then-President Charles Vest addressed by leveling up resources for women.

Female MIT faculty have also been slower to form companies at the rate of their male counterparts — something Hockfield attributes to "network effects." Among two men talking about a new idea, one might say to the other, "Let me introduce you to the person who helped me start my company and raise funding. And then you become another MIT entrepreneur," said Hockfield. "But that rarely happens for women. There are assumptions that men act this way, and women act that way."

To address this gap, Hockfield co-founded the MIT Future Founders Initiative in 2020 to increase the number of female faculty members who start biotechnology companies. The program includes Future Founders Boot Camp: a series of talks from successful academics who have started companies to translate technologies from their laboratories into therapeutics, medical devices and diagnostics for unmet medical needs.

"We have an incredible group of women serving as faculty founders. If women had been founding companies at the same rate as our male colleagues, there would have been 40 more companies, and that just makes me weep," she said. "That's when I decided I'm going to do what I can to help this initiative because we cannot squander our assets."

3. The Kendall Square neighborhood of Cambridge, MA was once destined to be a major site for NASA.

NASA's Electronics Research Center (ERC) was established in Cambridge, MA, in September 1964 to improve the electronics research capabilities for the space program.

"Kendall Square was cleared for that," said Hockfield. "But then Kennedy was killed and Johnson came in, and NASA's headquarters were established in Texas." The ERC closed in 1970 due to NASA budget cutbacks.

What happened, however, was that Kendall Square had a lot of open space. Biogen was one of the first to come in and set up shop.

"There was a little bit of pushback because biologics and bioengineering often look like Frankenstein to people," Hockfield contended. "But ultimately the City Council voted to approve the regulation of biologics. And that was the starting gun for the development of Kendall Square. It is chockablock not just with biotech companies, but technology companies such as Akamai."

MIT also owns real estate in the neighborhood, which makes up a significant part of the university's endowment.

4. Proximity and a common purpose nurture research and development ecosystems.

Hockfield explained that the biotech corridor in the Boston area and the Kendall Square neighborhood thrive because companies with similar purposes and goals are clustered together.

"If you lost your job in one company, you could just take the elevator down, walk across the parking lot and get a job in another company," she explained.

Proximity also makes it easier for people in biotech to interact. "You've got to be able to walk. You've got to be able to cluster. And people need to have places to have lunch and coffee together," she added.

New York City has the ingredients of a strong life sciences ecosystem: major universities with Nobel laureates, academic medical centers, and finance and investment firms —with plenty of places for interaction. "It will have its own inflection," Hockfield surmised. "It's hard for me to imagine it not happening. Doing things that are going to help people binds a community together in a very powerful way."

5. "Cure" can mean turning a life-threatening illness into a chronic disease, but more recently, it can mean banishing the disease entirely.

Hockfield is intrigued by the accomplishments made in gene and cellular therapies.

"The idea that we could engineer your DNA or cells to make a component that is intrinsically missing was once science fiction. But it is not science fiction anymore," she explained. "This new era of gene and cell therapy holds the promise of real cures. I have tremendous hope, if not optimism. I don't imagine there'll be anything but glimmers of progress over the next decade, and we are headed in that direction."